Nestled in the wilds of northern Japan there exists a clothing company that for years has been quietly and confidently making some of the best vintage-inspired clothing in the world. I’d heard bits and pieces about Deluxeware over the years, but because they haven’t had much of an overseas presence, I didn’t know a lot about them, even living here in Japan. After years of seeing their gorgeous stuff on Instagram, I reached out, explained who I was, and asked them if we could have a chat. “You’d better come up and see for yourself. I think that’s really the best way for you to see and understand what we’re doing”, was the reply from Hayato Muramatsu, Deluxeware’s founder and CEO.

Two flights later, I was met by Muramatsu-san at the tiny Odate airport in Akita prefecture and spent the next 24 hours learning and soaking up as much as I could about the history and current goings-on at Deluxeware and their factory (named Oldact). To say I was impressed would be an understatement, and in the midst of it all I found time to have a quiet sit down with the boss and hear a bit more about this little slice of heaven he’s built way up in the green cedar forests of Akita.

Muramatsu-san’s love of vintage items started early, mostly from reading the fashion magazines of the time, and he has fond memories of being 17 and scraping enough money together to take the 2-hour bus ride to Morioka, the nearest city that had an actual secondhand shop. He had in his hand a magazine clipping of a vintage pair of jeans, and wondered if he might actually be able to see the real thing. There, in a glass case, he spotted a pair of 1950s Levis 501XX that has remained seared into his memory every since. “I was just a kid with no means to buy anything, so of course they didn’t even want to take it out of the case for me”, he recalls. However, after repeated trips to Morioka, he finally convinced them to let him see this vintage pair directly, on the condition that he not touch them. He stared and stared at this gorgeous item, this thing of his dreams, and the fuse was lit.

Getting mostly bad grades in school, Muramatsu-san excelled in technical school and ended up getting a promising job at a major automobile manufacturer. It was an enviable position that promised steady pay increases and long-term stability. “I have no right to complain”, he would tell himself, though somehow knowing his heart yearned for more. He did his best to fit in and push down the creative feelings that welled up inside and urged him to create things on his own, but it was only a matter of time before that dam would burst. After seeing an a ‘vintage clothes buyer wanted’ ad in the local paper, he went against all common sense and quit his job. “Before they would let me resign, they made sure I understood that I was making a massive mistake, and would never get a job like this again in the industry. They said I would come to truly regret this”. But it was too late. Terrified and excited, Muramatsu-san gave it all up for vintage clothing.

It wasn’t the dreamland he had hoped for. “It was rock bottom, but it was there that I made the best friends of my life”, he says. “I was suddenly in a different world, a world of weird looking people and literally tons of vintage clothing to sort through every day. I learned a lot, but we were all living on the poverty line. I couldn’t afford kerosene for my heater, and we just lived on instant ramen or other cheap scraps, and at night I could only crawl under my futon to keep from freezing.” Years went by and there were many ups-and-downs, but he spend most of his little money on customizing cars, living in a tiny one-room apartment all the while. He became an expert at identifying vintage items, but when the American vintage boom started to die down, the company was downsized and he decided to leave. He was now unemployed and completely broke. It felt like there was nowhere to go, but the call of vintage clothing was not done with him.

After months of being unemployed, Muramatsu-san saw a small ad for an vintage clothing company in Nagano and called, asking for a job. They told him they were not hiring, but after trying again and again, they somehow hired him on. “I basically forced them into it”, he laughs. So, he left his friends behind after a tearful goodbye party down on the local river, and drove to Nagano prefecture in his 1977 Datsun truck with his few belongings in the back and nothing in his pockets.

“It was here that I realized that I really had no skills, and each day was a struggle”. He now had to deal with the public on a daily basis, and people laughed at his countryside accent. “I began to speak less and less so I wouldn’t make a fool of myself”, he remembers, “but I never gave up and I kept studying proper words and pronunciation until I got it. After a year or so, I knew this was a place I could be happy in. I was 24. I would start work at 9 even though we didn’t have to be there until 10, and sometimes I wouldn’t stop until 2 am”. Eventually recognized for his talents and never-give-up attitude, he was promoted. Things were starting to change, and he began to do serious design work for the company.

As is often the case however, there were internal struggles in the company, and despite his Hurculean efforts, things did not work out. “After working so hard for so long and having a massive project fail, I felt that their attitude towards me had changed. It seemed that no matter how hard I tried, the company would not trust me. I do want to say however that I am very grateful to them for nurturing my sales and design skills, even though it didn’t ultimately work out”. So he loaded that same old Datsun truck and went back home to an Akita that had visibly declined in the years he’d been away. “Depopulation and the low economy had taken it’s toll, especially in the countryside. It wasn’t a pretty picture.”

Forced to take a job as a waiter just to survive, he now longed to put the ‘vintage memories’ behind him, but one evening a customer commented on his unique clothing and wallet, all items he had designed himself at his previous job. “You’re into American vintage style?”, the man asked. “I felt such a surge of mixed feelings that I could only croak out, ‘Uh…uh…yeah’. What DID I like? I didn’t even know, but for the first time in forever I went to the convenience store on the way home to buy a vintage fashion magazine like I used to, and there on the pages was a feature on the items I had actually worked so hard to make at my previous company. I stood there and cried, right in the middle of the store. What was I doing? Who was I? I again found myself not being able to resist the call to do something I truly loved. “

Akita is famous for garment manufacturing, so Muramatsu-san began trying to sell himself to the different factories, offering to manage everything from design, to manufacturing, to sales. “But the answer was always, ‘We don’t need you’ or ‘Just go home’. This is where the drive to start my own company began”. He worked for a few more months at the restaurant and saved all his money to get a laptop and some secondhand software, and taught himself how to use Adobe Illustrator and other programs. “That computer saved me. I could do all of my design, flyers, calculations, graphs, a homepage on it.” With advice from the president of the company that owned the restaurant he was working at, he filed to incorporate as an actual company. “When I incorporated, I still remember what it said on the paper: Employees: 0, Capital: 0, Assets: one laptop. I actually did have 200 yen on me, but after buying myself a beer to celebrate my founding a company, I once again found myself with nothing.”

Did you start off here in Odate?

No. At first it was in my hometown, a little place not far from here.

So how did you go about collecting your vintage sewing machines at first? Especially way out here. Did you just slowly buy them, one-by-one?

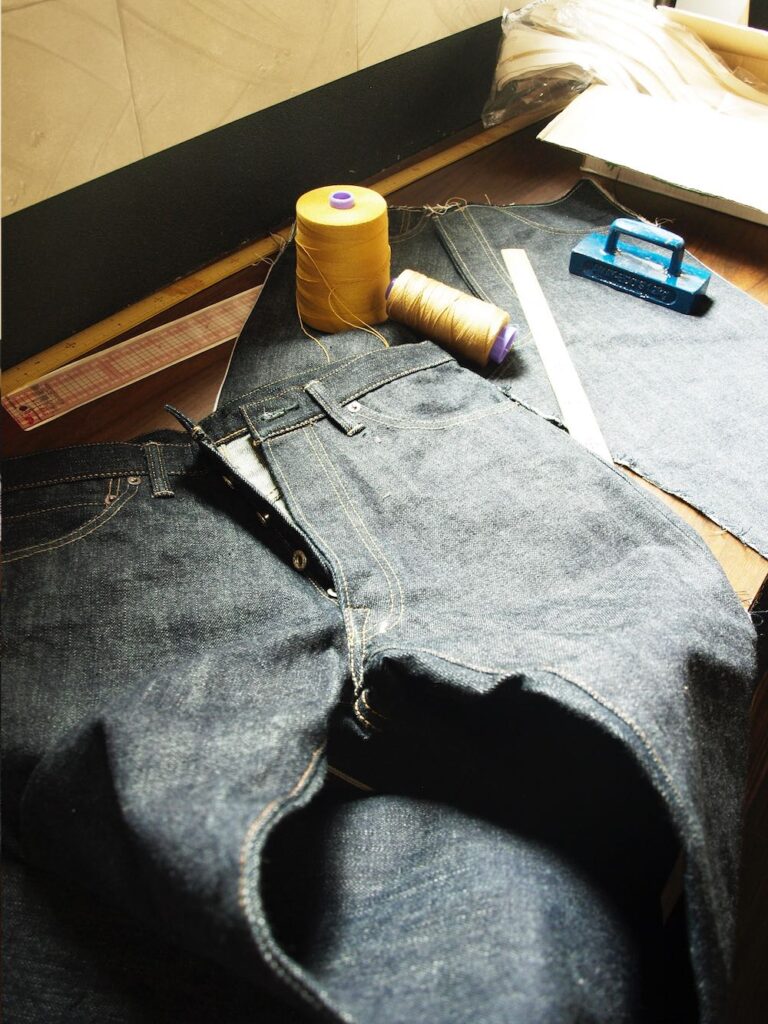

Well, that didn’t start until later, actually. At the very beginning, I wasn’t serious about having my own factory or anything like that. I didn’t really know anything about sewing machines then. For the first four or five years, I had my things made in other factories, but would be told things like, “We can’t do it” or I’d realize that I’d just end up losing money in the end. Nobody could make it just the way I wanted it anyway, so I just decided that this would be the time I’d give making my own factory a real shot. That was 2010. It was around then I really set out to start finding the perfect vintage machines.

Wow, that’s really cool. Did you have any idea how to use any of the machines you were gathering?

Nope, not at all (laughs).

How does one go about learning something like that? Machines that aren’t around any more?

For example, I’d find machine from the 1920s and 30s, and as you can imagine they were usually in pretty bad condition, like covered in dust, grease, or just all rusted. So they had to be completely cleaned and overhauled, and sometimes totally rebuilt. I didn’t do this – we have a sewing machine master technician around here who does it, but I would be there with him and I would learn as we rebuilt the machines: “Oh okay, this kind of machine does this kind of stitch. If I sew this fabric or this part, this is the result”. And it went like that, learning as we went for each machine. It was a fascinating process: restoring, teaching, and learning at the same time, and a different journey for each machine. And on top of this, we had to heavily customize the machines to do the kind of work we were wanting. That’s the great thing about the old machines; being made of metal they can be customized. No way you can do that with modern machines that use so many plastic parts.

Were there setbacks and hardships back at the start?

Oh wow, so many. Firstly, I was only 27 and at that time, as you know, there were already a lot of vintage brands in Japan that were well-established, all doing pretty similar things. So for me to be starting at that time was pretty late, and the conditions were not really favorable at all for what I was wanting to do. I couldn’t always make what I wanted, and on the selling end of it, the shops would say, “We already have a contract with so-and-so brand, so we can’t deal with you.” Brand loyalties are like that here. I just had to keep it up, and do my best and make small, one-by-one relationships and transactions. And eventually it grew from all that hard work and became more solid and steady, but you know, catching up to brands who were already running ahead of me when I started was a massive challenge.

How about the name, Deluxeware? It actually sounds pretty good in English.

It’s a word I made up, I guess. I think the meaning of “deluxe” is obvious, but the “ware” is not “wear” as in like “wear clothes”. It instead means “thing” or “item”. Back in the old days, TVs, motorcycles, cars, cameras, whatever, all had different models, different ranks. And often the top models would be branded the “deluxe model”. So we liked the meaning of paying homage to that time while also meaning that we too would aim to produce only the best items, whatever items they may be. It’s supposed to be a connection to the past as well as a present commitment to make only items that will last well into the future. Vintage items were build to last until now, and even beyond. We are also building things we want to last for many decades.

Yeah, it’s cool…the word itself and the meaning contained in it. Were you happy with what you were making at first, or was a long process of mistakes?

There were tons of mistakes, naturally. The first thing I ever made were T-shirts. Four different shapes. And it took me half a year just to figure that out – how to make four simple patterns.

What about jeans. Were you making them at that time as well?

No, that was later. I wanted to be able to do that perfectly, and I knew what would be involved, so I waited until I had the skills and means before I began tackling jeans. I guess I knew better than to just to dive into something that was beyond me at that time. I really wasn’t ready for that at the beginning.

Where do the ideas for all your stuff come from? Just you or do you also ask staff and customers for ideas?

From myself and the voices of our customers.

Do you find that customers can be pretty…how should I say it…’strong’ in their wants and wishes?

Oh yeah, for sure.

Do you find that Japanese and overseas customers differ in their wishes, expectations, complaints, style?

Well, to be honest, I can’t say I have a ton of experience yet with selling overseas or dealing directly with overseas customers, so I can’t really answer that. I’m not sure how they think, but our Japanese customers are fussy in a good way, looking at every part, checking the stitches for us. This always helps us, and their attention to detail makes it nice when they tell us we’ve made something really great because they actually do know what they are talking about. So I’m interested to see what overseas customers might be like, to what level they are interested in all the details, whether the levels of no-compromise we go to here will translate well for them. I’m looking forward to finding out.

You might be surprised, there are some pretty discerning overseas customers, too (laughs).

Haha…perfect, I’m expecting that.

Maybe an odd question, but are there any other denim brands that you like or appreciate what they are doing?

Hmmm…well, first and foremost I love vintage Levis. Lee. Wrangler. These are my big 3. But if you mean Japanese brands, then I’d first say Warehouse.

Do you see them as friends, competitors, or just people doing similar things?

Well, in Warehouse’s case, my feeling is that they are a vintage replica brand. Deluxeware is based in vintage wear, but we take the elements that we like and create something new, so in that sense, I don’t see us as competitors at all because we are doing different things. It’s tough to say (laughs)…that word “competitors”…in one sense, it’s kind of everybody, but in another sense we’re all doing something different.

What’s your favorite item you’ve made so far?

Our denim shirt.

The one you wore yesterday?

No, the 7640. It’s an original based on vintage elements. Cues from coveralls, all-in-ones, and denim shirts were all mixed together and it’s kind of our special item that really encapsulates what we’re about.

Are you still making it?

Of course, from the start to the end.

I’ll check it out. How many silhouettes of jeans do you have? And denim types?

For jeans, we have 3 cuts and 3 types of denim that we use.

All from Okayama, of course?

Yes.

Can you say the specific mills that you use?

Sure. Shinya.

That’s just at Shinya?

There is another place called Yamaashi.

How often would you get foreign customers coming into the store here?

Almost never. A few a year, maybe?

What are the best things and worst things about your job?

When a new product comes out and the customers love it. That is probably the best feeling. The worst is when we aren’t able to make what me want to make, when it doesn’t come out how we envisioned. That’s not fun at all.

Can you describe yourself? What kind of personality are you?

Haha…hmmm…that’s kind of hard to say about yourself. I’d say though that I’m pretty stubborn when it comes to quality, details, and not cutting any corners.

Can you describe that a bit more, that idea of ‘kodawari’, or being so particular that everything is perfect?

Like, if somebody is sewing, it might be saying, “I want it done this way” ????? up until 15:45.

What do you like aside from all of this stuff? Hobbies or interests.

It would have to be driving and cars. And customizing them.

Ah yeah, what was that car you showed me yesterday?

It’s a 1977 Datsun truck.

Those are super rare, even here in Japan. On your site, it said that your clothes are guaranteed? Or have a kind of warranty? Can you say a bit more about that?

Yes, it applies to all of our stuff. We believe that we are basically sending out products that are free of faults, but there might be a rare case where, to a particular customer’s eye, their item seems B-grade for some reason. We fix that for free. ????? up to 17:23

What happens currently if an overseas customer buys something from you and it arrives and it doesn’t fit?

Well, we just started really selling overseas, so that hasn’t happened yet, but within Japan we do free conditional exchanges. Conditional means that you can’t have worn it out or taken all the tags off it and then try to exchange it. With overseas, because the distances are so great, there is shipping to be taken into consideration. We are working on the details now, but if the customer ships it back to us, we want to work it out so that we can exchange sizes and make it right.

How are going planning to handle the difference in general body types between Japan and many overseas areas as far as your sizing goes?

We are now in the planning stages of making more larger sizes to address this.

Why haven’t you really branched out overseas yet? Your stuff looks incredible, and you’ve been at it for quite a long time. Were you waiting for something specific to happen?

We wanted to be able to do it properly. We didn’t just want to say, “Hey buy our stuff because it’s popular here in Japan”, we wanted to be able to actually show people directly and have them understand everything that goes into making our clothing before we tried to sell it to them. It’s also best if they can see it and touch it in person. That takes time to do it in the right way. It was also a matter of volume. We of course have to supply our dealers here as well, and we just didn’t have enough production capability to be able to keep our obligations going here while also selling overseas. We didn’t have that power, but we feel that now we are approaching that point where we can confidently offer things to the outside world.

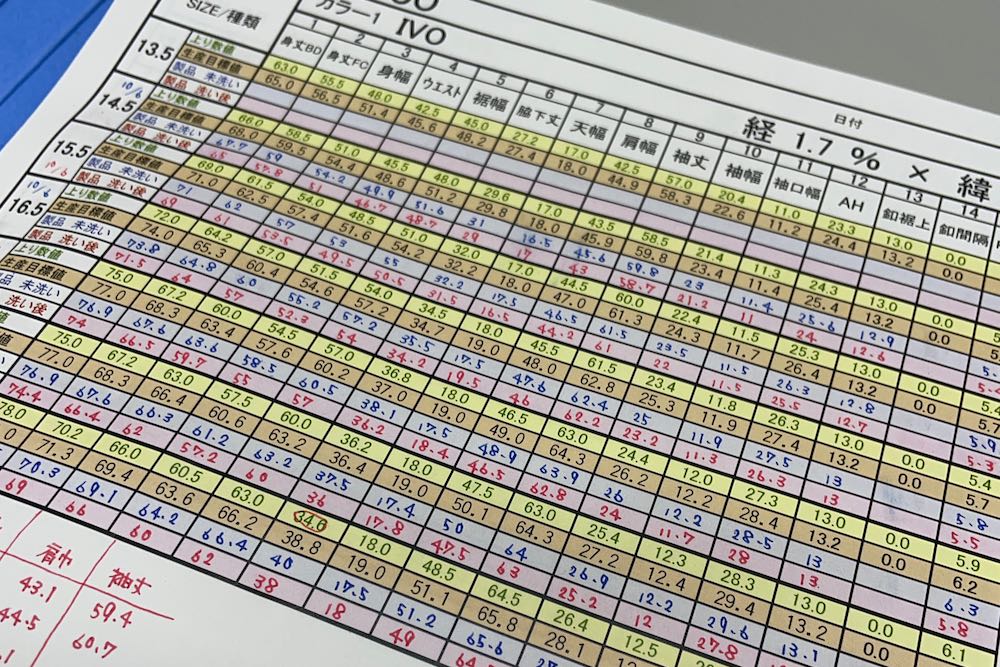

Can we go back to your idea of the concept of “kodawari”, or no-compromise? Those measurement sheets you showed me were beyond what most places do or would even think of doing. You were literally measuring, shrinking, and remeasuring every single piece of fabric for every model. That would take forever and is probably not totally necessary. Why do you bother going to that level?

“Kodawari” has many levels. We are particular about the fabric, about the machines, about the way we make things, about the silhouette…so many kinds of kodawari, right? Those detailed measurements are our proof of perfect construction, at every stage. It also a way of supporting the customer and making sure they get the exact thing they expected, with the numbers to back it up. A record trail exists for each item.

Is this for your own peace of mind or for the customer mostly?

Of course it helps us keep track of what we are making, but it’s mostly when and if customers have a question. We can tell them, “This fabric came from this place in Okayama. This size of needle and thread was used for this part. These were the exact dimensions before and after shrinkage.” Every part and process is recorded and kept. Nothing is hidden, and there is proof for everything. This proof is really important.

Akita is pretty far from everything. Has this been good for you or not?

Ah, yeah. Both, for sure. The good is that here, away from the hustle and bustle, we can really focus and concentrate on making the best product possible. The bad part is simply the lack of people. If you’re trying to sell something, obviously having more people around helps. We are pretty far out of the way here in Akita.

Is there anything else you’d like to say or have people know about you or the company?

Firstly, I’d like people to know and remember the name Deluxeware, and also what exactly it is that we are doing. I mean, I hope you will give us a chance to show you what we are making, and also how we are making it. I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised.

If I’m someone living overseas and I’m interested in your stuff, but have no way to see it, feel it, or try it, what can I do?

Yeah, that’s the challenge, isn’t it? Of course, people want to actually hold it and try it on first, right? Firstly, you can ask your local shop if they’d be interesting in stocking Deluxeware and we’ll see what we can do. It would be great to be able to do that kind of thing from now on. But we do have an English webshop now with a selection of items you can try.

Maybe for a lot of people out there, especially when they can’t see your products in person, denim brands can all look pretty similar. What, in your opinion, sets Deluxeware apart?

For us, it really is about quality. We want everyone to experience what real quality is, to give us that chance to show you what it really means. Turn it over, turn it inside out, and really have a good look.

We had that interesting talk earlier about “sanchi” or the areas in Japan that specialize in certain kinds of fabrics or items, much like the Bordeaux area of France has all these areas with slightly different flavour profiles and specialties. Can you talk a bit about that?

It’s kind of the same as fruit, in a way. Aomori means apples. Okayama means peaches. Tochigi is famous for strawberries, and the best oranges come from Wakayama. And in each of those areas, it’s not just that the best fruit is coming from each place, there are also very specialized technologies and production methods in those areas that make it possible. It’s the same with fabrics. So, everyone associates Okayama with denim, and they too have their own finely-crafted skills and technologies around that. With shirting fabric, it’s Niigata, Nishiwaki in Hyogo, etc. Chambray, flannel, etc., this is where you’ll find the best available anywhere. They have mastered the techniques surrounding those fabrics and have the best old looms for those particular fabrics. In Wakayama, they have the old hanging knitting machines for making loop wheel fabric, only four places left. I go to these places in person, talk with them face-to-face, get deep into the fabrics and come up with an original plan, using their specialty fabrics, to give birth to something special through our factory here at Deluxeware. I want to convey these regional ‘flavors’ to our customers through the medium of impeccably-manufactured garments.

That’s fantastic. I saw yesterday that just in your T-shirts alone, you sell them in 3 different fabric weights. That’s not something you usually see.

For us, it’s the same as jeans, in the sense that, just as there are different denim weights used for jeans, in the same way we use different fabric weights in our T-shirts too. Our thinnest fabric is incredibly elastic. Lightweight, but you can totally stretch it out and it just goes back to its original shape. The medium weight shirts are, as you can imagine, in the middle, a nice balance between being light and elastic but also having a little more heft, while the thick ones are 12oz monsters. It all comes from the old knitting machines, each one only being able to knit enough fabric for six shirts in a whole day. So we need those machines to be going all year long, and we customize the machines even further to make the fabric stronger. If our shirts stretch out within 3 years, you can make a claim with us.

It’s not common at all for a denim brand to have their own on-site factory. I imagine it’s mostly a good thing, but are there any difficulties associated with it?

The good thing is that there is no limit to what we can make. I don’t mean volume-wise, but we can make whatever our imaginations can come up with – total freedom. Also, it’s not like a static entity where things are always staying the same like if you were just putting orders in to an outsourced factory and always getting the same product back. What I mean is that we are constantly learning and refining our skills and techniques. So what we made today will actually make what we create the following day better; it’s like an exponential thing where the more we try, the better we get, which in turn means we can try more new things. It’s really great in that way, to be constantly improving. No limit to what we can do.

The ‘bad’ part is that having a running factory is very expensive. We have to obviously pay for this building, all the machines and maintenance, all the craftsmen’s salaries – it’s an enormous running cost. So yeah, the cost and the running of all the management systems necessary to run a place like this. Having a factory is one thing, but to actually be able to make a profit or at least enough to keep it going is a massive job. If all of this isn’t done perfectly, you won’t last long. I don’t want to make it sound like it’s all about money, but the reality is that you can’t run a place like this for long if you’re constantly in the red.

I guess, though, that having your own sewing factory doesn’t completely protect you from all of the hurdles and limiting factors that affect other brands, like wait times for denim production, limited amounts of fabric at certain times, etc.

That’s correct. The challenges are many. Like those production areas we were talking about earlier, all sorts of things can happen there. Like the guy who used to dye your thread has passed away, that particular denim mill has closed down, etc. So many points at which things can get tough, Something that was just there yesterday is suddenly gone. There are no guarantees things will be there tomorrow. It’s a worry that’s always on my mind.

I heard that a lot of the overseas workers that had been here working and learning in the factories went home when Covid hit, and then didn’t come back.

That’s true, but that’s not the only problem. The economy is the real issue. When people don’t feel secure about their financial situation, they aren’t thinking of buying high-quality items like Japan is producing. When that happens, the factories stop making fabric, and then people like us can no longer keep doing what we are doing. So we want people to enjoy and understand quality goods, and buy them with a good feeling in their heart and we can keep the whole thing going. Not in a wasteful way, but in an educated, sustainable way where people can understand and be proud of what they are buying and wearing.

In my experience, overseas people seem to know a lot more about Japanese clothing than most Japanese. Almost none of my Japanese friends outside of the industry even know Japan makes jeans. I wonder why? Such good stuff, right in their backyard.

I think they take it for granted, and maybe kind of forgot. To be honest, most younger people here now have no idea how clothing is even made. I’ve talked to some young people who literally think that clothing is produced by feeding fabric into a big machine that looks like a box and it all somehow gets instantly created inside by some complex process, and then the finished items just pop out the other side. Seriously! (laughs). This being the case, you can kind of understand why there isn’t all that much interest in or knowledge on the subject.

If I’m honest, I was actually kind of surprised at the prices of your stuff. I’ve seen a lot of stuff, and if we’re comparing similar items, Deluxeware seems about 10% cheaper on most things compared to many other Japanese brands. Why is that?

Firstly, we do everything ourselves. Normally, you would pay a design house to create your items, or you would use a middleman textile company to choose your fabrics for you, etc. We don’t do that. So we can do a lot of stuff in-house, and that reduces the need to use so many outside people or businesses, and this keeps costs down. Another reason is that our craftsmen here are highly-skilled, which also means they are fast. This makes a difference obviously if you are able to produce more and better clothing in the same amount of time when compared to other factories.

As we come to a close here, I’d like to circle back around to the idea of “kodawari”, or no-compromise. I don’t think a lot of the things you guys do will be noticed by people, even discerning denim fans. Like how you showed me that every stripe on that flannel pattern must match perfectly throughout the whole shirt: body, sides, yoke, collar, sleeves, and even cuffs…nobody goes that far. Is that level of insanity really necessary (laughs)?

For us, that is part of the quality of the item, not a separate thing. A discerning eye will know, and we want the customer to see, feel, and know they are getting the absolute highest quality possible, and so we go to those lengths. Because we want to make the best clothing possible, it’s not weird at all for us to do that. It’s kind of normal.

What do you foresee or hope for Deluxeware over the next 5, 10, 20 years?

I want to be known worldwide as a brand that makes the highest-quality Amekaji clothing possible. That’s my dream.

This has been a fascinating and fun talk, Muramatsu-san. In closing, is there anything you’d like to say in closing?

To everyone outside of Japan, nice to meet you. I’m Muramatsu from Deluxeware. We make the best clothing we possibly can, and we’d like you to try it. Feel it, wear it, fall in love with it. I hope you’ll give us a try, and I’d like to express my gratitude in advance. Thank you so much.

That sounds about perfect. Thanks so much.

Thank you.

English shop: https://www.deluxeware.shop/

Japanese site: https://www.deluxeware.net/

Pingback: An Interview with Deluxeware's Muramatsu-san - The Weekly Rundown